How to Stimulate the Vagus Nerve and Support Vagus Nerve Health

The vagus nerve is the 10th cranial nerve, extending from the brain through the cervical spine, heart, lungs, and gastrointestinal system. The vagus nerve is the longest cranial nerve and impacts the most organs in the body of any other nerve. It is the control center of the parasympathetic nervous system, which activates our rest and digest state — the state from which we achieve optimal health and wellbeing.

This is just scratching the surface of the vagus nerve, and already you can see how important it is for keeping our bodies healthy and functioning well. In fact, there have been some exciting therapeutic interventions developed over the last ten years or so that target the vagus nerve for some of the most devastating chronic illnesses, such as treatment-resistant epilepsy and inflammatory bowel disease.

But you don’t need to have a chronic condition to benefit from a healthy vagus nerve. Rather, supporting your vagus nerve can help ensure that your body lives from a state of homeostasis, or calm balance. So how can we support our vagus nerve health?

In this article, we’ll discuss the importance of the vagus nerve, how to know if you have good vagal tone, and how to stimulate an underperforming vagus nerve.

Table of Contents:

- The Importance of the Vagus Nerve

- Do You Have Good Vagal Tone

- When You’ve Tried It All, The Missing Key Might Be Your Vagus Nerve

- How to Stimulate the Vagus Nerve

- Nutrition for the Vagus Nerve

- Stimulate the Vagus Nerve Naturally

- Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS)

- Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation (tVNS)

- Healing Your Vagus Nerve

The Importance of the Vagus Nerve

The vagus nerve is responsible for transmitting instructions from our brain to many organs in the body, including the heart, lungs, stomach, and intestines. It can also receive signals from these organs and transmit that information back to the brain. The vagus nerve is a two way street. We often think of our brain as the control center of the body, but the gut, for example, has just as much input on how the body responds to certain stimuli (like food).

For example, if the gut is inflamed, the vagus nerve can sense and communicate that information to the brain (sometimes resulting in symptoms like brain fog).

The vagus nerve also plays a role in:

- Motor function: enervates the neck muscles, such as those used for swallowing

- Parasympathetic response: controls digestion, heart rate, and breathing

- The hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis: the HPA controls cortisol release and regulates hormonal balance

- Stress management: a lot of stress can overwhelm the vagus nerve, resulting in a vicious cycle that compounds stress over time (remaining in a state of fight or flight vs. homeostasis)

- Brain-gut and gut-brain communication

- Managing the fear response

- Modulating systemic inflammation.

Already you can see how people with mood issues like anxiety and depression, any gut-related conditions, and nervous system dysregulation, whether it’s extreme, like seizures, or something more common like dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), probably have an impaired vagus nerve in some way. The vagus is very sensitive to stress, and long periods of physical, mental, or emotional stress will very likely impact its function.

Do You Have Good Vagal Tone?

When the vagus nerve is operating well, we can say we have good vagal tone. Just like when a muscle is toned, it's healthy and strong. So, what are the signs of good vagal tone?

- Healthy digestion and motility: A key sign of healthy vagal tone is solid, clockwork digestion. You’re having a bowel movement every day, or ideally after every meal. You can easily digest your food. Constipation is a rare occurrence, if it occurs at all. This is a sign that your brain is communicating well with your gut and vice versa, all via the vagus nerve.

- You bounce back from stress easily: In an everyday stressful situation, you feel the impact of that stress, but it doesn’t overwhelm you or cause you to shut down in the moment. You can handle the situation and return to a calm state when it’s over. This is a sign that your vagus nerve can easily switch into a parasympathetic state after a sympathetic (stress-based) response.

- A generally content, peaceful mood: Basically, you’re chill. You operate from a calm, content, rational state of mind. When challenges come up, you don’t freak out or shut down, instead approaching the situation with a level head. Anxiety and depression are not really an issue for you.

How many of these describe you? Two out of three? One? Zero? If you struck out on all of these characteristics, you’re not alone. Many of us have chronic health issues like IBS, hormone imbalances, chronic constipation, and more that can throw all of these out of whack over time.

The good news is that supporting your vagus nerve can’t hurt, whether vagus nerve dysfunction is at the root of the issue or not. At the least, it’s a good idea to support the body’s ability to handle stress. And if you’ve tried a lot of different therapies to no avail, it might actually be the thing that turns the tide.

When You’ve Tried it All, the Missing Key Might Be Your Vagus Nerve

Let’s use an example of chronic constipation. Say you’ve been dealing with chronic constipation for several months, ever since you experienced an extremely stressful event. (Or a long period of stress… like a pandemic.) You’re lucky to go #2 every few days, and it seems like it’s getting worse. Your gut just doesn’t want to move. You’ve tried all the typical solutions: changing your diet, exercising regularly, taking probiotics, supplementing needed vitamins and minerals, and taking prokinetics like aloe or vitamin C.

But nothing has worked, and the constipation has you feeling irritable and easily overwhelmed. You used to be able to handle challenges that came up at work with confidence, and now you just feel like you’re always on edge and frazzled throughout the day. What’s the deal?

This is one situation where a vagus nerve-specific intervention may be helpful. When the vagus nerve is “offline” or not communicating with the gut, motility can slow down (or speed up, if it’s overactivated). In this example, this person experienced a highly stressful event that precipitated their symptoms. This may have thrown the vagus nerve for a loop and started a chain reaction of disruptions that eventually led to slow motility.

Reactivating the nerve might be the key to restoring this person’s digestion, their mood, and ability to handle stress. It can also allow all of those other therapies, like probiotics and vitamins, to work better. Now we’ll take a closer look at how to do just that.

How To Stimulate the Vagus Nerve

Stimulating, or regulating, the vagus nerve can happen through a number of pathways. It will come as no surprise that there are certain nutrients that support the vagus nerve, as well as activities. But for serious intervention, there’s also vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) or its less invasive cousin, transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS). Let’s go through these methods one by one.

Nutrition for the Vagus Nerve

Nutrients that support the vagus nerve include:

- Choline (to make acetylcholine, our main neurotransmitter)

- Vitamin B12

- Magnesium

- Calcium

- Sodium (yep, salt)

- Omega-3 fats.

Arguably the biggest player for vagus nerve health in this list is choline, used to make acetylcholine, the most abundant neurotransmitter in the body. Choline is absolutely essential for many functions of the vagus nerve.

Choline, which is neither a vitamin nor a mineral but typically grouped with the B vitamins, is an essential nutrient that we mostly get from eggs, red meat, liver, chicken, fish, and sunflower seeds. Animal foods are best to get dietary choline; most plant sources of this nutrient have very low amounts and may be poorly absorbed.

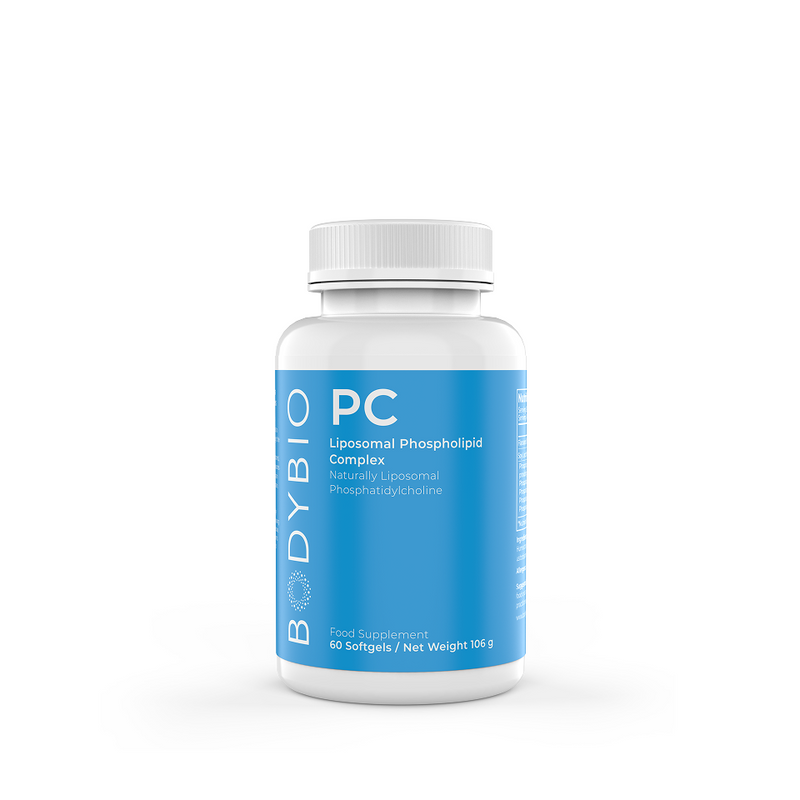

Fortunately, a high-quality phosphatidylcholine supplement can also supply choline (it’s right there in the name) when the body needs it. Upon taking BodyBio PC, the body can decide whether to break it down into choline and phospholipids or use it in its whole form in our cell membranes. Handy, right?

Another key nutrient to mention here is sodium. A study found that women on “high sodium” diets were found to have increased vagal tone via measurement of heart rate variability (HRV). This finding lines up well with recent research that salt — meaning real, mineralized salt — is actually key for full-body health and longevity.

Stimulate the Vagus Nerve Naturally

Other methods to stimulate and regulate vagus nerve activity include activities like:

- Yoga

- Deep, diaphragmatic breathing

- Meditation

- Singing, laughing, gargling, and humming (activating the vocal cords)

- Listening to certain sound frequencies (Safe and Sound Protocol).

Yoga, diaphragmatic breathing, and meditation all promote the mind-body connection. These activities all involve conscious breath, which stimulates the vagus nerve and promotes the parasympathetic nervous system.

Singing, laughing, and humming also physically stimulate the nerve, which runs parallel to the back of the throat. These vocal activities also involve breath control and may produce oxytocin, the happy hormone, so these aspects may also contribute to vagus nerve regulation.

The Safe and Sound Protocol (SSP) uses different sound frequencies to prime the nervous system (via the vagus nerve) and generate a sense of safety and calm within the body. This allows patients to process trauma effectively and regulate emotions and behaviors.

This system is based on the work of Dr. Stephen Porges, the founder of polyvagal theory, who showed that trauma responses and learned behaviors become integrated into the nervous system, and these responses can be more effectively healed with physiological or somatic therapies (as opposed to psychological interventions like cognitive behavioral therapy). Stimulating the vagus nerve via sound frequencies is one such physiological therapy.

Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS)

Vagus nerve stimulation involves surgically placing a small electrical device in the chest with a wire running to the vagus nerve in the neck. Through the device, a low-level electrical current is transmitted to the nerve, stimulating its anti-inflammatory and nervous system-calming effects.

Though it’s an invasive procedure, traditional VNS has proven effective for treatment-resistant epilepsy, inflammatory bowel disease, and even severe depression. Needless to say, most of us aren’t going to have access to such a procedure, not to mention the risks involved with any surgery and an implanted medical device. Fortunately, there is a non-invasive method that uses the same electrical stimulation to enervate the vagus nerve — through the external ear.

Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation (tVNS)

Transcutaneous (auricular) vagus nerve stimulation uses a TENS device. TENS devices have been used for decades and have wide clinical applications for reducing pain and relaxing tense muscles. The TENS device can be hooked up to a lead that attaches to a small clip. This goes on the tragus, part of your outer ear.

Through this pathway, the vagus nerve is stimulated similarly to an implanted device. So far, research has shown promising results for this novel and significantly less invasive electrical therapy for many conditions. Also, whereas traditional VNS is a continuous therapy, tVNS can be employed for short sessions up to a few times a day, minimizing the risk of any side effects that come with constant stimulation.

Research and clinical trials are still being conducted to determine the efficacy of tVNS in many conditions, but current research looks promising. For example, in a trial with 34 patients with clinical depression, half were given tVNS treatments and half were given sham treatments to serve as a control. In the true tVNS patients, significant improvements were measured in functional connectivity in the default mode network (DMN) of the brain, part of the brain responsible for self-representation and emotional processing.

Additional studies have been conducted on patients with:

- Lupus erythematosus, resulting in reduced pain and fatigue

- Stroke, improving upper limb and sensory function

- Tinnitus, relieving symptoms

- Cardiovascular disease, modulating the state of autonomic dominance (stress) that often accompanies many heart conditions.

Further studies with tVNS are being conducted on fibromyalgia, inflammatory bowel disease, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and even early treatment for neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s disease. The potential therapeutic applications for tVNS are diverse and truly exciting.

But, if you’re not interested in this type of therapy, diet (especially choline and macrominerals) and lifestyle changes (yoga, meditation, and deep breathing) can be equally profound when implemented over time.

Healing Your Vagus Nerve

For some people, vagus nerve healing can be instrumental to improving symptoms of chronic illness, promoting the brain-gut connection, and maintaining a calm, consistent baseline mood. You can support the vagus nerve through your diet and supplemental nutrition, movement and exercises like yoga and meditation, and even novel approaches like tVNS.* Whatever method works best for you, supporting vagus nerve health is critical for a healthy body and mind.

Want to dig deeper? Read more about the gut-brain connection here.Marshall, R., Taylor, I., Lahr, C., Abell, T. L., Espinoza, I., Gupta, N. K., & Gomez, C. R. (2015). Bioelectrical Stimulation for the Reduction of Inflammation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clinical medicine insights. Gastroenterology, 8, 55–59. https://doi.org/10.4137/CGast.S31779

Aranow, C., Atish-Fregoso, Y., Lesser, M., Mackay, M., Anderson, E., Chavan, S., Zanos, T. P., Datta-Chaudhuri, T., Bouton, C., Tracey, K. J., & Diamond, B. (2021). Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation reduces pain and fatigue in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled pilot trial. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 80(2), 203–208. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217872

Butt, M. F., Albusoda, A., Farmer, A. D., & Aziz, Q. (2020). The anatomical basis for transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation. Journal of anatomy, 236(4), 588–611. https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.13122

Cunningham, C. J., & Martínez, J. L. (2021). The Wandering Nerve: Positional Variations of the Cervical Vagus Nerve and Neurosurgical Implications. World neurosurgery, 156, 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2021.09.090

Bonaz, B., Sinniger, V., & Pellissier, S. (2017). Vagus nerve stimulation: a new promising therapeutic tool in inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of internal medicine, 282(1), 46–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12611

Cork S. C. (2018). The role of the vagus nerve in appetite control: Implications for the pathogenesis of obesity. Journal of neuroendocrinology, 30(11), e12643. https://doi.org/10.1111/jne.12643

Yuan, H., & Silberstein, S. D. (2016). Vagus Nerve and Vagus Nerve Stimulation, a Comprehensive Review: Part I. Headache, 56(1), 71–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12647

McNeely, J. D., Windham, B. G., & Anderson, D. E. (2008). Dietary sodium effects on heart rate variability in salt sensitivity of blood pressure. Psychophysiology, 45(3), 405–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00629.x

Baig, S. S., Kamarova, M., Ali, A., Su, L., Dawson, J., Redgrave, J. N., & Majid, A. (2022). Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS) in stroke: the evidence, challenges and future directions. Autonomic neuroscience : basic & clinical, 237, 102909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102909

Clancy, J. A., Mary, D. A., Witte, K. K., Greenwood, J. P., Deuchars, S. A., & Deuchars, J. (2014). Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation in healthy humans reduces sympathetic nerve activity. Brain stimulation, 7(6), 871–877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2014.07.031

Yakunina, N., & Nam, E. C. (2021). Direct and Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Treatment of Tinnitus: A Scoping Review. Frontiers in neuroscience, 15, 680590. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.680590

Carandina, A., Rodrigues, G. D., Di Francesco, P., Filtz, A., Bellocchi, C., Furlan, L., Carugo, S., Montano, N., & Tobaldini, E. (2021). Effects of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on cardiovascular autonomic control in health and disease. Autonomic neuroscience : basic & clinical, 236, 102893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102893

Steidel, K., Krause, K., Menzler, K., Strzelczyk, A., Immisch, I., Fuest, S., Gorny, I., Mross, P., Hakel, L., Schmidt, L., Timmermann, L., Rosenow, F., Bauer, S., & Knake, S. (2021). Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation influences gastric motility: A randomized, double-blind trial in healthy individuals. Brain stimulation, 14(5), 1126–1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2021.06.006

Zaehle, T., & Krauel, K. (2021). Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A viable option?. Progress in brain research, 264, 171–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pbr.2021.03.001

Ko D. (2021). Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS) as a potential therapeutic application for neurodegenerative disorders - A focus on dysautonomia in Parkinson's disease. Autonomic neuroscience : basic & clinical, 235, 102858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102858